It was a packed house at the Embassy Suites Hotel in Saratoga Springs for the Diversity Symposium of Thought Leaders sponsored by NYSCOSS.

Fostering Equity in Unequal Times

Lack of racial and ethnic diversity among educators is a problem that can and must be solved. That was a key theme at a symposium hosted by the New York State Council of School Superintendents in Saratoga Springs.

The daylong gathering drew more than 130 superintendents, assistant superintendents, school board members, and other educators to Saratoga Springs to learn about issues involving equity; the idea that treating all students the same does not achieve fairness. Instead, students from different backgrounds need different levels of support in order to help all reach their potential. Achieving more diversity among faculty and administrators can be a step forward because students flourish when they have role models they can identify with, according to presenters at the event.

The conference highlighted findings of the recently released “See Our Truth” research report from The Education Trust–New York that provided statistics highlighting the lack of diversity among teachers in New York state schools:

- Ten percent of Latino and Black students – more than 115,000 – attend schools with no teachers of the same race or ethnicity.

- Latino and Black students in districts outside of the Big 5 (Buffalo, New York City, Rochester, Syracuse, and Yonkers) are nearly 13 times more likely than their Big 5 peers to have no exposure to teachers of their same race/ethnicity.

- Nearly half – 48 percent or 560,000 – of white students are also enrolled in schools without exposure to a single Latino or Black teacher.

The result is an education system that deprives students of color of adult role models who can inspire the self-respect and confidence that leads to improved educational outcomes, according to Dr. R. Oliver Robinson, Superintendent at Shenendehowa Central School District, and one of the organizers of the conference.

It also deprives white students of exposure to educators who can model the advantages of diversity to help change attitudes in a way that will improve outcomes for all students, Robinson said. He added that greater diversity among educators also provides students with a more holistic view of the more global society they will enter upon graduation, be it college or career.

The conference was the fruit of months of planning by a commission on diversity within the Council created by outgoing president Patricia Sullivan-Kriss this past summer.

Kelly Masline, senior associate director of the Council, said the ultimate goal of the 26-member group is to sustain an ongoing effort to increase diversity among educators and help create a pipeline for advancement for minority educators who can make a difference for students.

The majority of teachers in the state are female, said Masline, and while 30 percent of superintendents are women, only three percent of superintendents are people of color in the local district positions that have the potential to facilitate the most change.

“My kids don’t have one teacher who’s diverse, and that’s very common,” said Masline. “This commission has that issue of how do we get more diverse individuals into the teaching field so they have that chance to advance?”

Taking personal action to foster change

Two of the main presenters for the event were part of that three percent demographic cited by Masline. Both are superintendents who have had first hand experience with the challenges faced by educators of color in making changes that improve outcomes for students.

Dr. Luvelle Brown, superintend at Ithaca CSD, grew up himself in rural poverty in Virginia. His father never graduated from high school because as an African American, he wasn’t allowed to attend the local school. Brown dedicated his own education career to working in rural communities for that very reason, and spent his early career in rural districts in Virginia before coming to Ithaca in January 2011. He oversees a district of 6,000 students drawn from urban, suburban and rural settings.

He sees the same kinds of problems in New York schools that he faced in Virginia, and the same need for local educators to step up to lead changes. But he admits it won’t be easy. For him, the See Our Truth report validated what he had already seen himself.

“Not only are we not making progress, in some ways we are regressing,” he said, and that makes the need for educators to stand up and speak up more important than ever.

The situation was highlighted for him personally in 2017 when he was named superintendent of the Year by the New York State Council of School Superintendents (NYSCOSS). His mother attended the ceremony, said Brown, and after the ceremony “She looked around and said to me ‘They can give you all the awards they wish, but you’ve done nothing until you change the way this room looks.’”

He surveyed the audience that was mostly white and male, and “I vowed to do something that was actionable to change things,” he remembers.

Small group members discuss their experiences during the afternoon breakout session. From left to right: Eudes S. Budhai, Superintendent, Westbury CDS, Maria Rice, Superintendent, New Paltz CSD, and Ken Slentz, Superintendent, Skaneateles CSD

Now Dr. Brown assertively tells his fellow educators they have to ask each other tough questions about the current climate, where he says many public institutions with predominantly white male leadership project an image of racism, classism, and sexism. Then, he added, they have to bring those questions to their communities to help change ideas and policies that have created a situation where it’s difficult to recruit educators of color to rural areas where their own perceptions and biases may make them fear they won’t be welcome.

“As educators, we are risk averse and conflict averse, and because of that we fail to engage in conversation that are uncomfortable. Are we prepared to lead those types of conversations in our communities? Nothing is going to change until you change policies. It’s going to require us to be self-reflective, trustful, truthful, forgiving, and dedicated in all things that create discomfort and conflict.”

Dr. L. Oliver Robinson, Superintendent at Shenendehowa CSD, shares Brown’s conviction that educators in leadership positions have to take an active role in changing ideas and policies to improve equity and, ultimately, educational outcomes for students. He agrees with Brown that may be hard for some.

“The status quo is comfortable, and people like to be comfortable,” said Dr. Robinson. “Anytime you challenge the norms people think it’s an indictment of the system. I’m not challenging to blame, but to change folks and ask the real question of why is it not working? Why are those populations of students not being successful?”

Robinson thinks it’s also helpful to keep in mind the meaning of equity as it relates to education.

“Equity by definition is treating differences differently. In the context of education, it starts with the recognition that students bring different skills, experiences, and expectations to the table, and it is vital that we take the time understand, appreciation, and act upon them in a way that empowers their growth as learners and sense of significance as a person.”

“Operationally, it means looking at how we are serving students and asking the critical question of what else can be done to help improve the quality of program and services. At the end of the day, it is about yielding equity in outcomes, meaning it doesn’t matter the background, race, creed, religion, preferences; all students are provided ample opportunities for success and sufficiently supported.”

Along with Dr. Brown, he also agrees that recruiting more educators of color is important both for leadership roles and classroom teaching to improve outcomes for students of color.

“There is a lot of research to establish that when kids see role models like themselves, they have confidence in who they themselves are. How do we do that in a systemic way that’s not just politically correct or currently popular, but is in a way that is what public schools are supposed to be about?”

Educators also have to be willing to try new methods to change the mindset of both staff and students, said Dr. Robinson. Ten years ago in his own district there was not a single black student in the district’s high school AP program. After asking himself why the most challenging courses had such little diversity, a check of the program’s gatekeeper requirements revealed that some students were prohibited from enrolling based on academic performance items going as far back as sixth grade.

So the guidelines were revised. Staff encouraged students with the academic background to enroll, but any interested student was also allowed to enroll if they showed a willingness to do the work.

There was some pushback, he said, but the bold move worked. From 2013-2017, AP enrollment increased almost 50 percent, 84 percent of those students scored a 3 or above on AP tests, and the school now has more merit scholars than ever.

He says such questions–and the new ideas they generate–are part of what educators need to ask themselves about current policies and ideas.

“What are the messages we send to kids? Those subtle messages that we don’t even realize system wide what we’re doing?”

Making a difference through authentic relationships

Sean and Nicole Eversley Bradwell have first hand experience with some of the tough questions that educators must ask themselves and each other, and the positive results that can come from the conversations.

Dr. Eversley Bradwell is Director of Programs and Outreach at Ithaca College, and Mrs. Eversley Bradwell is Director of Admissions at the private liberal arts college with 6700 students. Dr. Eversley Bradwell is also vice-President of the board of education for Ithaca CSD. The couple has lived in Ithaca for over 20 years.

In 2015, ongoing discussions of diversity at the college culminated in student protests that led to resignation of the president and a re-examination of how the school approached the issue. Today a series of initiatives have reshaped the diversity related landscape. The school now has a Diversity Officer, required training for staff, revised hiring and staff manuals, and other measures to facilitate discussion and innovation that leads to real change in attitudes and systems.

The Eversley Bradwells stress that for all educators it’s important to both facilitate discussion and create what they called “authentic” relationships–in person, real life exchanges with those who may well have differing opinions.

“If we can’t be in the same space and recognize one another, then we’re not going to be able to work together well,” said Nicole. “We are in such segregated times, and for many it’s easy to get into a space where everyone thinks and talks and look just like you. Our media is being served up to us based on what we click on, so if you don’t want an alternative perspective, you can do a pretty good job of avoiding it unless you’re willing to build those authentic relationships. We really have to be purposeful if want to engage with others and learn and grow with others who have a different perspective.”

The conversations that do that don’t come easy to many educators, said Sean.

“Most of the time, folks have significant difficulty having general conversations of any kind, let alone conversations centered around diversity and inclusion. But without the dialogue, there’s no room for the innovation.”

“There’s also incredible risk in these conversations. People are afraid of saying the wrong thing, offending people, using the wrong terms. A teacher one time told me she purposely avoids interactions with people of color for fear of being called racist. That’s huge cultural capital there, if your biggest worry is that someone may think you’re a racist or call you a racist.”

He added that it’s also often difficult for teachers to deal with the perception they should be open to new ideas, which can conflict with balancing the needs of a whole classroom of students in front of them.

But the Eversey Bradwells hope the presentation they made at the symposium, with its five talking points to keep in mind, will spark conversations and relationships that will lead to change in a state where more than half of students are of color, but only three percent of superintendents are.

“That’s a pretty big disconnect,” said Sean.

Small changes can make a big difference.

Superintendents in particular are in a unique position to facilitate change through their legislated authority, and even through smaller daily tasks such as delivering the morning message to students.

That’s one of the methods used by Dr. Deborah Wortham of Ramapo CSD to help instill self-confidence and belief in success to students in her diverse district, where 99 percent of the 9,000 public school students are either Hispanic or African American.

While the message is usually only about two minutes long, it starts students off with positive reinforcement, cultivating diversity and equity every day, and she depends on her teachers to continue that message to students.

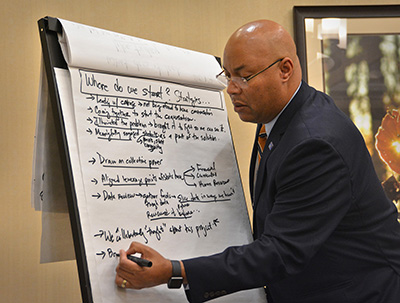

In the afternoon session, attendees separated into small discussion groups to brainstorm ideas on how to address diversity issues in their local districts. Here Mathis Calvin III, Superintendent in the Wayne CSD, helps record group member’s ideas for discussion.

“We are first and foremost teaching confidence, knowing that your belief matters,” she said. So with confidence, when you believe that you can achieve, then you will work hard. And when you work hard, you have evidence of success, and you will achieve.”

Other attending educators also had their own accounts of how successfully opening lines of communication around diversity can lead to improvements in student outcomes. Juan Mendez, superintendent of New Visions for Public Schools (The Bronx & Queens) & District 28 High Schools recalled how one short conversation with a male African American student traced his academic problems in English to the student’s frustration at the lack of educator role models in a department staffed exclusively with white female teachers.

“They don’t look like me,” he told Mendez.

A conference with the department’s assistant principal to address the issue led to an active diversity recruitment program. That in turn led to improved student scholarship rates and regents test performance, and an overall increase in student achievement levels.

Because of one conversation “we changed the whole perspective,” he said.

Masline said the conference exceeded her expectation and the commission is planning to expand its work to a regional level. They are also making preliminary plans for another symposium July 30-31 at a location to be announced.

“I’ve been here for twenty years and I think this is one of the best things we’ve ever done. We are a small staff, but I think the timing and need for this is more critical than it’s ever been. It’s something we really believe in.”

This story originally appeared in the January 22, 2018 edition of On Board, the newspaper of the New York State School Boards Association.